Cave Drawings In The Tassili

1974 commentary by Loomis Dean

On Easter Sunday, 1974, we set off from Paris for the southernmost part of the Sahara, about 2,000 kilometers south of Algiers, through the desert and the vast Tassili mountain range. The trip down there is an adventure in itself, over the full length of the Sahara as we know it. We flew in an ancient old Convair, re-equipped with powerful Rolls Royce turbo-jet engines for short takeoff’s and landings on those desert airstrips. The plane only stops once between Algiers and Djanet, our destination. In the grammar school geography books, it is claimed that there is only 7% desert area in the entire world, which is sand dunes, but from our altitude, which wasn’t high since ours was not a pressurized plane, it looked like sand dunes all the way. Actually it was just flat shale rock; barren and miserable with nothing to see for the 2,000 kilometers.

On Easter Sunday, 1974, we set off from Paris for the southernmost part of the Sahara, about 2,000 kilometers south of Algiers, through the desert and the vast Tassili mountain range. The trip down there is an adventure in itself, over the full length of the Sahara as we know it. We flew in an ancient old Convair, re-equipped with powerful Rolls Royce turbo-jet engines for short takeoff’s and landings on those desert airstrips. The plane only stops once between Algiers and Djanet, our destination. In the grammar school geography books, it is claimed that there is only 7% desert area in the entire world, which is sand dunes, but from our altitude, which wasn’t high since ours was not a pressurized plane, it looked like sand dunes all the way. Actually it was just flat shale rock; barren and miserable with nothing to see for the 2,000 kilometers.

We passed over the Hassi-Messaoud oilfields; the first oilfield found in Algeria about 10 or 15 years ago. Until then they had never had a drop of oil, but now it is one of the largest oil producing countries in the world. I had been through Hassi-Messaoud by jeep about 15 years before, but from the air it’s like flying over Saudi Arabia with thousands of those gas jets burning. I couldn’t recognize anything which is not unusual in the desert anyway, as there are no landmarks. We found that out on our way back in a sand storm.

We flew all day long; a 6 or 7-hour flight from Algiers to the area we were starting from where the cave paintings are located near Djanet and the Tassili mountain range. The remote little airstrip at Djanet has no tower, radio or anything, and you just hope you can land there because the next landing strip is 600 miles away……providing there is enough gasoline.

We landed at Djanet in the middle of nowhere, and miraculously Landrovers appeared to pick us up and drive us into town. After flying thousands of kilometers without seeing a palm tree or blade of grass, Djanet appears as a true oasis situated on a dry riverbed and when water collects there they can grow vegetables, grain wheat, and millet; whatever is needed to feed the goats and camels.

The so-called “hotel” looks quite romantic; set in the middle of a palm grove and all the rooms are constructed just as the Touaregs build their houses, made of 12 to 15 foot tall reeds that grow in the wet river bottoms. It looks just like a house of straw , which is exactly what it is, but we didn’t quite realize how comfortable it was with running water, flush toilets and supposedly cold beer until we returned a week later after camping in the desert.

We had expected it to be roaring hot down there but we found it pleasantly cool. As a matter of fact, all the advance information you get, seems to be false. We heard all kinds of nonsense about the Sahara; supposedly boiling hot in the day and below freezing at night and I was prepared for the worst, and was agreeably surprised. We took showers, washed our clothes, and ordered some beer which resulted in the first real hassle because the icebox had broken down and there was no cold beer in all of Djanet until one afternoon when a German expedition showed up. These tourists arrived in three old German World War II sort of Dodge power wagons; huge weapon carriers converted into expeditionary vehicles and loaded with all sorts of mechanical equipment to keep them in repair. When we told them the icebox was broken, they instantly fixed it, and an hour later we had the cold beer. Mind you, to get that beer there at all, it had to be trucked over 2,000 kilometers over a road which is paved only half way down with the last part full of ruts in the middle of the desert.

All expeditions to see the cave paintings start from Djanet, which is at least a town of sorts and does have stores and a telephone, although it is a radio-phone. Djanet was formerly an old French fort.

We spent one night there and set out the following day equipped with a whole list of nonsense prepared in Paris with the help of the Algerian Tourist office and a fat little bureaucrat who had never been there. Few tourists ever go to Algeria anyway and the last one was probably Eldridge Cleaver who may or may not still be there. Algeria is definitely not tourist oriented yet, although they are building beautiful hotels in all the oases near the coast. Everyone is still scared of the government and the handfulof tourists at Djanet were French; adventurers, artists, and college students interested in the cave drawings.

We were slightly apprehensive that the evening in Djanet when an expedition that had been out to see the caves returned. I have never seen such a beat-up bunch of people and even a ten-year-old girl appeared to have aged thirty years, and her father looked even worse with a four day growth of beard.

We felt pretty good after the cold beer and dinner of camel meat and couscous; went to bed early and set out at 5 A.M. the next morning after a good night’s sleep in that wonderful air.

It is almost impossible to get any precise information from anyone down there. We knew that if the jeep was not available we would have to walk or ride by camel or donkey back; whatever. We did get a jeep, or really a Landrover, for exactly five miles after which the driver stopped and said “Everybody out”, and there they were; a string of donkeys lined up at the foot of the biggest mountain I have ever seen in my life. They unloaded all our stuff; the sleeping bags, water bags, flashlight and a little sack with a change of clothes, packed into one giant duffel bag which is carried by a donkey. We had left our suitcases and other clothes in the hotel at Djanet.

I had reduced my belongings to the minimum but naturally had my camera case with me which is pretty damned heavy. We had bought ourselves some high lace-up tennis shoes and just hoped we would not turn our ankles. Ali, our guide, was dressed in a big black turban, sandals, and those baggy Arab britches. The others in the party of twelve were all French; men and women.

I was shocked when I realized where we were going; straight up the side of the mountain with those switchbacks, and I didn’t think we were going to make it. I hadn’t gone a hundred yards before that camera case got awfully heavy. It was solid rocks straight up and I was coughing, gasping, and choking. They were still packing the donkeys down below, and after about half an hour the guide called the first rest. We were so tired we couldn’t believe it but knew that this was just the beginning. When the donkey train caught up with us I made my first bright decision and unloaded the camera case, keeping what I thought I would need in my pocket. The donkey train had started half an hour after we had, but passed us before we even began to walk again.

From 5 A.M. until noon we walked 20 kilometers straight up that mountain and across a plateau to the base camp, the starting point for the cave drawings. The tents were quite comfortable and the cookhouse had all sorts of supplies brought up by donkey caravans. They served a lunch of canned food and we all sacked out forfour hours although the tents were hot and stuffy in mid-afternoon. However it was cool outside under an enormous Cypress tree at the altitude of about 7 or 8,000 feet. Around 5 P.M. we started out again to see the cave paintings and it stayed light until 8 P.M. or later. Walking on the plateau was much easier.

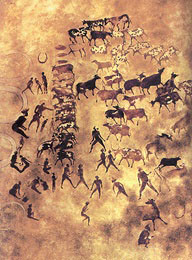

The paintings are not really in caves but in great overhangs or rock. They might have been actual caves at one time but have been worn away. The paintings have been renowned since the 1930’s and the Algerians are terribly jealous of them. Various expeditions visited them from time to time; Italians, the National Geographic, and remote French priests. All you need to photograph the paintings is a wet rag as they are covered with dust. An Italian expedition not only had wet cloths, but oily ones to wipe the surface of the drawings to give them contrast. You can get a much better picture that way. The Italians also had lights though it was not really necessary, but I certainly would have used a wet rag. However the Algerians would have not part of that, being rather suspicious of us since America still had no diplomatic relations with Algeria. Even though we had been officially invited on this trip, it took almost three weeks to obtain the visas.

We saw hundreds of paintings on the first day and I photographed everything in sight until I realized there were so many. Then I photographed only the contrasty ones, forgetting the flat drawings. I tried all sorts of tricks you can do with color film, but it was not a patch on finding one that was really old and contrasty. These rocks were sort of ochre-colored and the paintings were almost the same shade, so you saw red on red which isn’t all that good. However, the first day was quite successful and the second day about ten times better.

It’s cooler in the mornings and we started off again at 5 A.M. the next morning. Actually it’s not hot until the middle of summer and these trips take place six months a year from November through March or April. In spring it was not unduly warm and very stimulating to walk across that wild moonscape type country early in the morning. It’s daylight about 4 A.M. and I awoke early to try and get some sunrise pictures with a little color. I got up at 4:30 but it was already too late.

We felt much stronger after the first bad day, and the twenty-kilometer walk on the second morning was exhilarating in the clear air and profound silence. The scenery is astonishing with the wild fantastic shapes of those mountains in the Tassili range. One ascent was pretty steep but after that it was more or less flat although you had to watchwhere you put your feet on the flaky rock surface. One couldn’t really enjoy the scenery because you were always looking at your feet for fear of turning your ankle. If you sprained an ankle or got sick up there I don’t know how you would get down.

We carried water bags on our backs; long pork chop shaped bags with a spout on them like wine bags, and I was taking a sip about every ten feet. Some of the other climbers were trying to be Spartan and taking a sip about once an hour, but the rule is that if you’re thirsty in the desert, drink, which I did. Curiously, at that altitude, you don’t perspire even though I was taking a swig every few minutes. The water was rather rancid, having been transported from Djanet and then by donkeys up the mountain but we put a couple of pills in each bag and it was perfectly drinkable.

We got to our second base around noon and camped out that night with no tents in an extraordinary place with hundreds of rock overhangs. The donkey boys had arrived hours before and had a hot lunch prepared; primitive, but it tasted awfully good followed by hot tea. We had another long nap until the cool of the evening and set out to see other cave drawings. This was one of the most extraordinary places with all those drawings. What were they doing there and who made them? There are many conflicting versions. Again I only photographed those that really showed some contrast. I showed the guide a silk handkerchief from my pocket and asked if I couldn’t flip it over the paintings to dust them off. He was horrified. I also had a squirt bottle of water and was tempted to give a little spray but lost my nerve. The guides are pretty nice fellows but I didn’t dare take the chance of being abandoned up there.

This tour in the late afternoon was marvelous because the flies let you alone; millions and millions of flies being the only real hazard on this expedition. How they get across the desert and live with no water is anybody’s guess but they cover your back while you’re walking. If you slap them with a stick or handkerchief they just buzz around your face. You climb or walk in single file and you see that the back of the person ahead is literally covered with thousands of flies. They don’t bother the Arabs but are a nuisance to anyone else who is not used to them. All one really needs to cross the Sahara is a sack of water and some insect repellant, but among all the idiotic items I was told I’d need, insect repellent was not included. If we’d had one of those squirt cans of Citronella or something which shakes the mosquitoes down in Florida, the trip would have been far easier.

On the third day we walked back to our base camp by another route with more cave drawings all the way. The scenery changes constantly; it’s so extraordinary one can’t describe it. At noon we met the donkey boys who had been there and hour or so and had another a great lunch prepared; again about three courses and including salad and cassoulet. And it took some doing to have gotten tomatoes and lettuce up there. After lunch we slept again under the overhang of one of those huge caves and took off again in the late afternoon to reach base camp around dark.

The next day we started early and took a long easy route back to Djanet, reaching the haven of a hotel room around noon. We all went in the shower baths, a series of ten stalls, and just stood there; men and women together and nobody gave a damn about anything except getting wet and soapy. Then we washed all our clothes and dipped into cases of ice-cold beer, thanks to the Germans.

The following morning we flew to Tamanrasset which is the end of the world. The guides had wanted to take us to Tamanrasset from Djanet by Landrover over 600 kilometers of barren desert, and camping out 5 or 6 nights. I asked ”Why the hell are we going to Tamanrasset?” and they replied “This is part of this whole wild southern area of the Sahara. As long as you have come this far, you might as well see it all”. “But what has it got to do with cave drawings?” I queried. “Nothing” came the reply, “But there are some weird engravings on the rocks”. We were beaten to death by this time and I had had enough. “Can’t we get there some other way. Can’t we fly?” “Of course” they answered. “An airplane goes there every day.” “That’s it” I said. “If we want to get to Tamanrasset, we don’t care what’s in between. Once there, we can see the Hoggar Mountains”.

Tamanrasset is about as far away as you can get; sort of “Katmandu South” and wouldn’t you know the hippies had found it. Actually you have to give them credit for getting there at all. They don’t fly; they hitchhike on trucks or pay for their rides on supply trucks which bring almost everything to that remote part of the desert over paved roads or trails which are often drifted over by sand. When the roads are completely drifted over, the trucks navigate by compass, and all those bottles of beer we had been drinking had been trucked 2,000 or more kilometers over the roughest country in the world. The hippies seem to set faraway goals for themselves and there they were, sitting around with their beards and sandals, just talking. From there they go to Niger on to Rhodesia, and eventually back to civilization.

Tamanrasset was an old French army fort and the entire town is painted ochre in color. The French planted giant Tamarisk trees to shade the wide streets, bazaars, and the cattle markets. Eventually they are going to put in a Holiday Inn or something comparable there, but currently there is not a drop of water.

Refugees from Niger and the southern tip of the Sahara where there are terrible droughts, have migrated up to Tamanrasset which is supposedly an oasis. But they have now exhausted the wells. The hotel has private baths; even bidets yet, and not a drop of water. They claim that the water is on for one hour a day, but you never know just when that hour is going to be, and it’s really only on for the maids to take buckets of water and flush the toilets which have been accumulating all day. Once the toilets have been cleaned, there’s no water for anything else. Personally I would rather have one functioning flush toilet than ten naked redheaded girls fanning me with feathers.

There are roads of sorts leading out from Tamanrasset to the magnificent Hottar Mountains and we set out in a Landrover and stayed in a hostel at the top of a 10,000 foot mountain. After that we wanted to leave and return to Algiers the next day.

The flight was another adventure and I was plenty scared. I’ve been lost on airplanes in the South Pacific with dumb Air Force navigators who couldn’t navigate, but in this case they were skilled commercial crews who got lost in a sand storm. It took us twelve hours to do a six-hour trip. We were lost for six hours and finally clawed our way back to the starting point at Tamanrasset. The pilot candidly explained that we were lost and said “Don’t worry about a thing. We have about an hour and a half of gas left and will find someplace to land.”

They were trying to return to Tamanrasset which had a radio as all those other little desert airstrips didn’t have anything. The pilot explained that there was a magnetic field in the South Sahara and compasses became completely inaccurate, adding that “We are completely lost right now and have overshot Tamanrasset by and hour and a half. Nowthe sand storm has lifted a bit however, and we can get some visual contact.”

In the southern part where the mountains are located, there is something to see but elsewhere for thousands of square miles there is nothing and no landmarks to navigate by. The sand storm extended for about 2,400 kilometers and we could see nothing in any direction. We finally managed to land at Tamanrasset, refueled, and flew back to Algiers. And that’s the end of the story.

However, if you have any inclination for archeology and adventure and are interested in the cave drawings and some of the most remote places in the world, I would suggest Tassili; that is if you are up to walking about a hundred kilometers across the southern Sahara.